Enforcement

Long-term management of ICs requires adequate enforcement tools to promote compliance and protect receptors from an imminent or potential threat of from a release or exposure. A legal framework supporting enforcement will clearly communicate to a potential obligated party (OP) the consequences of a violation of an IC. In addition, enforcement tools should be progressive, consistently applied, and promote confidence that the IC enforcement process is administered responsibly. A sound IC legal framework provides notice to the OP of potential enforcement action for violations, legal defensibility of the IC, a transparent and defined process for the execution of enforcement actions and, ultimately, deterrence of IC violations.

▼Read more

Purpose of a Compliance and Enforcement Program

An IC enforcement model can follow traditional environmental enforcement models for water, air, and waste. For example, Connecticut has authority to enforce ICs that is similar to enforcement models commonly used in other areas of environmental enforcement (see Conn. Code §22A-133P (2015)(Connecticut). The authority allows for judicial action upon violation of an IC, leading to injunctive relief and the recovery of penalties of up to $25,000 for each violation. Connecticut’s code also provides for a gravity based evaluation of penalties, mitigation, and criminal enforcement.

This model potentially lends an IC enforcement credibility because of the relative familiarity in the regulator and regulated communities to these enforcement processes. Similar to traditional enforcement strategies, IC violations may be based on their seriousness (duration, magnitude, and culpability) and their impact or threat of impact to human health, the environment, and the interference with the effective administration of an IC program.

▼Read more

Challenges to IC Compliance and Enforcement

An effective IC enforcement program promotes certainty in the legal process; however, currently no model legal framework supports this goal. Twenty-three states and Washington, D.C., and the Virgin Islands have enacted some form of UECA (ASTSWMO 2015). Although UECA provides language allowing for a “civil action for injunctive or other equitable relief for violations,” it does not provide any specific legal framework to promote compliance and deter violations (Commissioners 2003). The model language provides only for conventional, common law relief once a violation occurs. Common law relief presumes judicial action is required to enforce.

▼Read more

Compliance and Enforcement Options

Enforcement According to Authority

Enforcement may be different, depending on the authority employed. For example, periodic reviews can result in a “pass” or “fail” of monitoring requirements. If a site passes a periodic review, the review is made available for public review and comment, and another review is scheduled in five years. A site fails a periodic review if it is determined that the remedy is not protective of human health and the environment. In this event, there may be several options for enforcement. First, correct the problem within a short time frame (for instance within 30 days) and incorporate the correction into the review. If the problem cannot be corrected in short order, then the site may be “reopened.” For sites in a Voluntary Cleanup Program, this means a no-further-action determination may be rescinded. The responsible party (RP) may then be required to correct the problem and re-enter the Voluntary Cleanup Program or referred for enforcement action. Second, formal sites under an order may require the RP to re-enter negotiations to correct the failed requirement.

Planning for a potential enforcement action is completed at the time of development of the IC, even though an IC holder may never be in violation. Effective enforcement of an IC depends on thoughtful IC planning. For example, if the enforceability of each specific IC requirement is not addressed during the planning and selection stage, then the enforcing entity may not be able to require compliance. Enforcement action may be considered when IC requirements:

- have not been observed;

- have not been implemented or fail to meet requirements;

- have not been adequately maintained or monitored;

- fail to have required certification; or

- fail to meet reporting requirements.

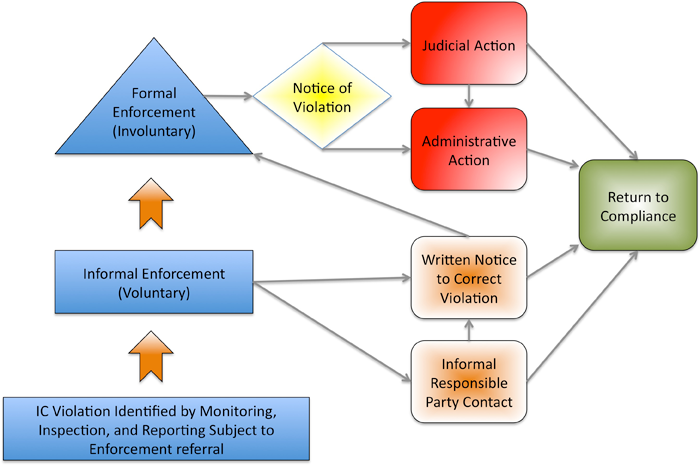

Once a violation is identified through monitoring, inspection, reporting or an IC performance evaluation, a basic IC enforcement model may be divided into two phases, including informal (voluntary compliance) and formal (involuntary compliance). Both are part of a progressive system to achieve corrective action of the IC violation. Figure 6 illustrates this system.

Figure 6. Basic model for enforcement process.

▼Read more

Optimizing Enforcement and Construction of a Basic Model

A compliance and enforcement strategy that effectively deters violations is fundamental to the success of long-term management of ICs. Effective enforcement tools are progressive, consistently applied, and provide sufficient notice to an OP that failure to meet IC requirements will be addressed with escalating and potentially costly enforcement consequences.

Planning for an IC enforcement action should take place at the time site-specific IC requirements are developed to carefully evaluate enforceability, interested parties, jurisdictional requirements, and methods of enforcement. Enforcement planning should occur as early as the development of a LTS Plan and should include, at a minimum, a thoughtful analysis of the following:

- all relevant authority to enforce, including statutory, administrative and common law authority

- all parties with authority to enforce, including an understanding of their respective interests

- a coherent process to enforce that is consistent, progressive, and responsibly applied

- an understanding of what circumstances trigger violations and when to enforce

The construction of a basic IC enforcement model can be premised on traditional environmental enforcement models for water, air, and waste, lending the IC enforcement program to familiarity and the credibility of an already established precedent. These enforcement programs employ a progressive, phased approach, including informal (voluntary compliance) and formal (involuntary compliance), that can be applied to IC enforcement and the achievement of corrective action.